In 1981, George Azar traveled from UC Berkeley to Beirut, Lebanon to see the Arab-Israeli conflict first hand. He got a job as a stringer, photographing the Lebanese civil war for the Associated Press and United Press International. He was captured by the Israelis during the 1982 invasion and taken to Israel, where he was released in Jerusalem. He returned to Lebanon and continued photographing the war until 1984. As the thirtieth anniversary of the Sabra and Shatilla massacre approached this year, Azar returned to Beirut to search for the people in some of his most memorable photographs. His story, and the story of his subjects, is explored in the film, “Beirut Photographer,” to be broadcast on Al Jazeera English as part of the documentary series Witness, beginning 5 December.

While many photographers documented the string of Lebanese wars from 1975 to 1991, George’s commitment to live in Beirut from 1981 – 1984, during a period of intense violence and turmoil stands out. He was not just another foreign photographer parachuting in for a few weeks to create sensational, action-packed images. Although he is clearly attuned to the political complexities and concerns of the multiple parties and groups in the conflicts of the region, his main interest has always been in individuals – whether they were street-level fighters or non-combatants caught up in events they had no control over. The large number of photographs of children and young people in his Lebanon work also speaks to a real empathy for their particular situation. But he never slips into pathos. He never asks for the viewer’s pity. Rather he depicts them directly and simply as they struggle to come to terms with violence, while also remaining children – happy, full of bravado, frightened, playful. It is his dedication to depicting the lives of ordinary people that really makes his work live on, whether he was photographing war in Lebanon, the Intifada in Palestine, or making documentaries around the region.

The photographs included here are samples of his work from that period. Jadaliyya co-editor Michelle Woodward spoke to George about his experiences both in the early 1980s and in 2012.

George Azar: During that period in Beirut there was a core group of combat photographers, and we were all friends, more or less. Learning photojournalism alongside them was one of the best things about being there for me. During the war, we traveled in groups of two or three, in case one person was wounded and needed help. Most of the time we were on assignment for competing news organizations, like the AP and UPI, or Time and Newsweek. We thought that no matter what you find, different sensibilities are at work - so the pictures are going to be different. And it always worked out that way. I learned by traveling with Catherine Leroy, the great Vietnam-era photographer who covered the Viet Cong; Alfred Yaghobzadeh, one of Iran’s most celebrated war photographers; Eli Reed of Magnum, and the list goes on. Don McCullen was there, and later James Natchway, the two preeminent war photographers of our time. I watched how they worked, what they looked for, and how they treated people. The one thing they all had in common was that they loved pictures and the life lived taking pictures.

The story as defined by the news organizations employing us was always essentially the same. Beirut = War. The sub-story changed from time to time, as did the players: the PLO, the US marines, Hezbollah, hijackers, kidnappers. As individual photographers, we were free to follow our interests. But the market, then and now, highly values “bang-bang,” dramatic images of violent combat. Many of us were focused on the fighting and the quest for the ultimate bang-bang image, with encouragement from our employers. When I first started working in 1981 and 1982, network TV crews had body armor and helmets, but none of the photojournalists wore them. By the mid-1980’s photographers started wearing Vietnam-era marine flack jackets with an old tin pot style helmet on occasion, as I did when covering the battle of Souk al Gharib. But, since I always want to blend in as much as possible, not disturb the normal dynamics of the situation, and to share the life of the people I’m filming, I generally don’t like to wear body armor unless shells are really falling nearby.

Gradually, I recognized that working for a big news magazine was essentially feeding the fires of propaganda and disinformation. It was hard to stomach the editorial line. About the same time, I realized that while my early photography was pretty strong in its depiction of the front line war experience, it didn’t reflect any of the things I loved about Lebanon: the humor and spirit of the people, or the physical beauty of the country. So during my next major period, in Palestine during the first Intifada, I made a conscious decision to take time to photograph the things I loved about Palestine in the context of the political struggle.

I was very reticent to return to Beirut this year with the photos I had taken in Lebanon 30 years ago. I expected the subjects to be angry with me for photographing them at such vulnerable, horrible moments. I was conscious that I’d frozen that moment forever, and I didn’t imagine it would be anything like giving them a gift. So I was really wary of coming face to face with the Takkoush family on Rue Jean d’Arc in Hamra for example. It was hard for me to step through the door to their shop. To make matters worse, one of the first things Badr said to me was, “Oh yes, that was the day my son died.” I felt the same reticence meeting the family of the young Palestinian fighter, Samir Salamon, who was killed days after I took his picture. However, they were all very pleased to have the photos. Each held them in a tender way, and you could see they were being transported back to the moment of the photo. Watching them regard the photos so deeply as physical objects reignited my appreciation of still photography.

I made the documentary film “Gaza Fixer” seven years ago while I was living in Gaza working on assignment for the New York Times. It is a film about covering the news. It was my first documentary, and it opened up a new world for me. Since then, I have done my photography with a video camera. I try to bring the aesthetic and practice of photojournalism to film. “Gaza Fixer” gave me the chance to make additional films, so, since 2005, I hadn’t felt an urgent need to take still pictures.

But the experience of making “Beirut Photographer,” of going back and pulling these pictures out of the shoebox, renewed my appreciation of the single still frame. They are simple, and pure, and true. So I am really happy that I have taken out the camera again. Freezing a fraction of a second allows you to understand a moment, an event, in a unique way that is different from, and complementary to, cinema.

The physical search for the people in the pictures was really interesting. It was like a detective story. When Al Jazeera commissioned the film, I thought to myself, “Oh, great. How am I going to explain that I couldn’t find any of the people?” I sensed that the whole film would be a disaster, or at very least, the story of a fruitless hunt for people long disappeared. So I was shocked we were able to track down anyone. We found people by physically covering the same ground, walking the streets, handing the pictures around, asking questions, networking. That was great fun and really rewarding.

It is hard to describe how surreal it was for me to be in places that held such deep and disorienting experiences, trying to be in the present moment filming the scenes unfolding, while at the same time being flooded by memories of the same place in the past. It was like seeing two images superimposed upon each other, like a double-exposure in photography.

[West Beirut, on the Green Line, in the Chiyah neighborhood, 1984. Photo by George Azar.]

I met these kids in February 1984 during a battle that was raging in West Beirut between Amal and the Lebanese army. They were the defenders of a neighborhood that straddled a strategic crossing point, right on the front line. In order to film in the heart of a battle, it helps if you know a particular group of fighters who will take you in with them and allow you to essentially become an “embed.” I followed them as they ran from alley to alley through destroyed houses, under tank and shellfire. We had some close encounters with death, and several of the Army of Chiyah kids, or the “Smurfs” as they called themselves, died while I was with them.

The two youngest boys, Zutti and Jawkal, were fourteen years old and orphaned when the Israelis killed their parents south Lebanon. They came to Beirut and lived in an area known as Sector 25, near Gallery Sam’an. During lulls, they climbed up on the rooftops and became snipers firing down into ‘Ayn al-Rummana, the adjoining neighborhood. They used to play music on a cassette recorder to pass the time between shots.

Their relationship to the war was different than the older boys, since they never knew a time before war. They had a different, more matter of fact relationship to violence. This is Beirut’s war generation.

The search for the Smurfs was complicated by the fact that their political groups, Amal and Hezbollah, are still in a state of war with Israel, and there are very real security barriers to prowling around Beirut’s southern suburbs with a camera. It was a huge break to get permission to do so. Once I was able to locate the leader of the Smurfs, Ali “Castro,” I had my guide to that past. We walked the streets of the neighborhood with an iPad and a stack of pictures finding each of the spots and sharing them with the people in the neighborhood.

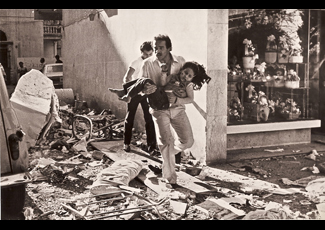

[Aftermath of a blast next to the Takkoush flower shops, Rue Jeanne d`Arc, 1982, Beirut. Photo by George Azar.]

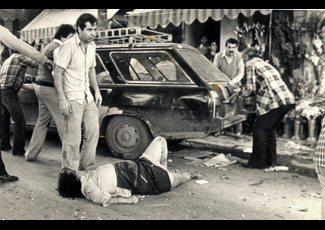

[Madame Takkoush after the blast next to the Takkoush flower shops, Rue Jeanne d`Arc, 1982, Beirut. Photo by George Azar.]

MW: In 2012, when you took these photos to the Takkoush flower shops, you found the shop proprietor and his wife, who is shown on the ground in the photo above. You thought she was dead but actually she survived. She didn’t think it was herself in the photo.

GA: The main reason she didn’t recognize herself is that she normally wears a hijab, and the woman in the photo had a pile of hair showing. It was only later, after her son pointed out her gold bracelets, that she realized that her headscarf had been blown off by the blast and that the woman lying on the ground was herself.

At the time I could not see how she could be alive, but I also did not focus on her. There was so much going on at the time…the noise, the smoke and general commotion, people running all about, the screaming. With the cameras of the period, you had to calculate exposure and manually focus. Later, I learned how to keep my head and clearly see what was going on, as if it was in slow motion. It is a trick to see frames among chaos, while not forgetting shutter speeds and f-stops, focusing, and all that.

[Fatah fighters, Baddawi camp, 1983. Photos by George Azar.]

The picture of the blond PLO fighter with RPGs and his friend with a Kalashnikov was taken one morning in 1983 during the battle of Baddawi Camp. Smoke turned the sky dark. We had breakfast of sugar tea and bread. Then the fighters organized themselves in pairs. One with RPGs, and the other with a Kalashnikov, and in a group of about eight or ten they marched off to fight the Syrian/Abu Musa forces. I have a picture of them marching away. I never saw them again. When I went back to Baddawi in 2012, these two teenagers were among the first people I looked for. The old fida’iyyin said that these guys were part of a contingent of fighters from the Palestinian camps in Syria who joined Yasser Arafat in Tripoli.

[Um Jalal & Khaled Marzouk and family under fire in a house in Jiyya during the Israeli invasion, June 1982. Photo by George Azar.]

MW: The boy on the lower left in this photo remembered you from this moment in 1982 and asked you in 2012, “Why did you leave us at that moment?”

GA: His question had two levels of meaning, both of which were disturbing. On one level he was saying that as the adult male, we looked to you to take care of us. During the battle, I had made sure everyone was low and away from flying glass and metal. I had taken charge during the shooting and he expected that I would stay with them. Then, after the Israelis rolled over our position, they took me away. On another level, when he asked why did you leave us at that precise moment, he was saying that all these years they wondered if I was a spy who flipped once the army arrived on the scene of this important battle. Lebanon was full of spies. I have seen spies posing as photographers more than once. All he remembered is that I appeared at the moment of the Israeli attack and then left with them. At nine years old he could not grasp that I was being taken away against my will. So he feels a lot better about me now.

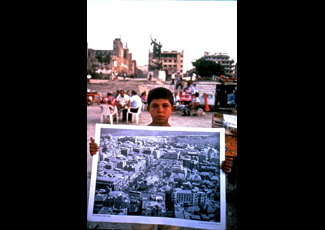

[Vendor at Martyr`s Square, Beirut, 1992. Photo by George Azar.]

I never found the kid I searched for first and last during our ten days in Lebanon. I do not know his name, and I think of him as the “Chiclets boy,” after the brand of gum kids sell on the streets. I took his picture on my first visit to downtown Beirut after the end of the war. I was walking around in a kind of trance, it was near sunset, the light was beautiful, people were out playing cards, smoking arguila in the magnificent square that was absolutely shattered, and it looked horribly beautiful with all its bullet holes in a cinematic way. I had only known that place as a free-fire zone where you had to run and duck the bullets, so it was amazing to walk around freely, watching people enjoy themselves. Then I saw a kid selling photos. When I looked at them I saw it was Beirut before the war, and he was standing in the same spot under the statue. I took this simple picture of a kid selling memories at the end of the war. I never saw him again.

Being given the opportunity to return to Beirut and make a film covering my personal terrain there and more interestingly, an era of Palestinian and Lebanese history that shaped today’s world, was a huge privilege. I just hope I told the story well.